“You never really own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation . . . ” As advertising slogans go, they don’t come more successful than Patek Philippe’s; it has served the Swiss watch brand for 20 years – eons in the fickle and ephemeral world of advertising – and graced The Atlantic magazine’s list of the best ad campaigns of all time.

In fact, this sentiment of luxury that lasts a lifetime (or, indeed, several) resonates today more than ever, as affluent customers increasingly lean toward meaningful, timeless purchases. Product longevity is fast becoming as important as aesthetics.

There’s still no shortage of people spending on expensive goods, of course, but disposable luxuries have lost their luster in this post-recession era of conscious consumption. Many consumers have reassessed their overall values and what investing in luxury really means. They have also been shocked by grim statistics about the cost at which their covetable purchases come.

For instance, the fact that up to 95 percent of clothing that ends up on landfill sites could be recycled or repaired, or that extending clothing life by just three months can reduce carbon, water and waste footprints by up to 10 percent, according to research by anti-waste charity WRAP. Key influencers have been adding their weight to the tide of opinion, such as iconic fashion designer Vivienne Westwood urging people to “Buy less. Choose well. Make it Last.” And one of the most tangible examples of this step-change is the rise of product preservation and aftercare services.

Few places are as synonymous with the allure of the new as the glossy stores of Fifth Avenue, New York. Yet if you step inside the Coach flagship store, opened in fall 2016, you’ll find a space dedicated to complimentary leather care and cleaning. Dubbed the Coach House Workshop, it’s the first of its kind by the U.S. brand. Star of the show will be a resident master craftsman with nearly 30 years of experience working in Coach’s studio headquarters. It’s a similar story in London’s luxury department store Harvey Nichols, where the redesigned accessories floor gives over valuable floor space to a Handbag Clinic run by a local repair specialist. Options include cleaning and weather protection for arm candy old or new.

In these ways, major brands are playing a more active role in extending the lifespan of their products. It’s not just a case of being able to get a faulty product fixed if under warranty (something they have long offered to customers); they are instigating creative complimentary initiatives to revitalize well-loved luxury goods and making these services part of their stores.

Katie Baron, Head of Retail at trend forecasting company Stylus, has observed a decisive shift toward such post-purchase services. “Today, true luxury is expressed as a definitive move away from the rampant consumerism of the mass market,” she says. “It’s largely fueled by attitudinal shifts towards more sustainable modes of business . . . For brands it’s emerging as a powerful tool for cultivating longer and more meaningful relationships with affluent consumers.” Naturally, any initiative that incentivizes store visits is gold dust in an age where physical retail must compete against e-commerce.

Another example she cites is Hermès’ series of laundry-themed pop-ups from September 2016. Running in Kyoto, Strasbourg, Amsterdam and Munich, “The Hermèsmatics,” invited visitors to take advantage of a complimentary scarf-refreshing service, regardless of the brand. Whether it was a vintage Pucci print or last season’s H&M, scarves were given colored rinses in the on-site washing machines and returned to their original softness in a special dryer. “Unusually inclusive for the luxury sector, it’s an example that also demonstrates how the notion of product preservation is being used strategically to entice a younger generation of luxury-curious consumers who could later transition from brand fans to prestige-sector spenders,” Baron adds.

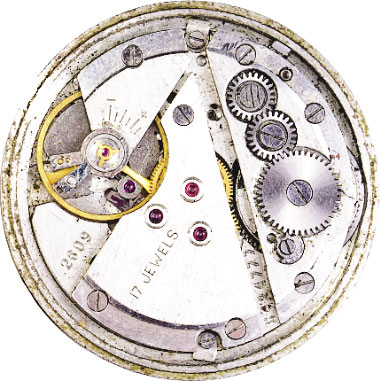

Here in Cayman, purveyors of luxury goods are keying into the mindful luxury movement with their own post-purchase services. Take Island Jewellers, for example. As well as carrying watch brands such as Ulysse Nardin, Hermès, Ball, Oris, Cuervo y Sobrinos, Tissot and Movado, the 40-year-old company services older watches and repairs pieces when parts are available – all part of a commitment to the mechanics of watchmaking. The services are carried out by the highly trained, third-generation watchmaker, Adrian Fernandez.

“Adrian is a genius,” declares Sales Manager Bob Nickoles. “He’s capable of servicing a 1950s Rolex or a highly complicated Ulysse Nardin Perpetual calendar – he’s that good.” Lasting luxury in watches is a theme Nickoles knows well: “When I sell a watch like Ulysse Nardin, it will probably stay in the family for generations. A well-made mechanical watch will run for many, many decades if properly serviced, and I love knowing that future generations will enjoy a family heirloom.”

“Adrian is a genius,” declares Sales Manager Bob Nickoles. “He’s capable of servicing a 1950s Rolex or a highly complicated Ulysse Nardin Perpetual calendar – he’s that good.” Lasting luxury in watches is a theme Nickoles knows well: “When I sell a watch like Ulysse Nardin, it will probably stay in the family for generations. A well-made mechanical watch will run for many, many decades if properly serviced, and I love knowing that future generations will enjoy a family heirloom.”

Island Jewellers’ concern with sustainable, ethical luxury runs beyond repair work, however, extending to the original sourcing and manufacture of pieces. Its diamond buyer only purchases diamonds from vendors who adhere to the Kimberley Process, which demands members ensure their rough diamonds are “conflict-free.” One example Nickoles gives is the brand Hearts on Fire, which “aside from being the world’s most perfectly cut diamond . . . happens to be one of the most ethical and credible manufacturers.”

Island Jewellers’ concern with sustainable, ethical luxury runs beyond repair work, however, extending to the original sourcing and manufacture of pieces. Its diamond buyer only purchases diamonds from vendors who adhere to the Kimberley Process, which demands members ensure their rough diamonds are “conflict-free.” One example Nickoles gives is the brand Hearts on Fire, which “aside from being the world’s most perfectly cut diamond . . . happens to be one of the most ethical and credible manufacturers.”

Similarly, Kirk Jewelers will steam clean jewelry, replace lost stones and refurbish watches.

The process of restoring precious goods to their former glory can be a true labor of love: it took the Audemars Piguet workshop team in Switzerland 800 hours to restore a damaged 19th-century double complication watch, and master horologist Michel Parmigiani labored for 2,000 hours to return an 18th-century Breguet pendulum clock to its former glory. Then again, it can be as straightforward as a polishing treatment to remove dullness or light scratches from regular wear.

Magnum Jewelers is the exculsive retailer for Audemars Piguet in the Cayman Islands.

Cartier’s exhaustive list of jewelry maintenance options, for instance, runs from complimentary Rapid Shining in one of their boutiques (involving cleaning in an ultrasonic tank and enhancing shine with a felt disk) through to Transformation (whereby an extremely damaged Cartier piece can undergo reshaping, resetting and replating). There is a comparable range of options for leather goods, writing instruments, watches and lighters. It would seem there’s no such thing as a lost cause.

Ethical luxury is poised to become ever more prominent in customers’ minds, especially as a new generation of luxury shoppers comes of age. A global study by Nielsen found that already 66 percent of online consumers across 60 countries are willing to pay more for products and services provided by companies committed to positive social and environmental impact, rising to an overwhelming 82 percent among Generation Z (those aged 15-20). With this we can expect to see the idea of product longevity evolving further, spawning more stand-alone concepts or business models that extend the lifespans of luxury goods.

Ethical luxury is poised to become ever more prominent in customers’ minds, especially as a new generation of luxury shoppers comes of age. A global study by Nielsen found that already 66 percent of online consumers across 60 countries are willing to pay more for products and services provided by companies committed to positive social and environmental impact, rising to an overwhelming 82 percent among Generation Z (those aged 15-20). With this we can expect to see the idea of product longevity evolving further, spawning more stand-alone concepts or business models that extend the lifespans of luxury goods.

A sign of things to come, designer denim brand Nudie Jeans has already had success launching dedicated repair shops in London, Berlin and New York that carry out free alterations and mending. The company has estimated it rehabbed 40,000 pairs of jeans by the end of 2016.

Meanwhile, Sweden-based Filippa K is one of the first fashion labels to open its own second-hand store. The boutique in Stockholm retails pre-owned and vintage Filippa K clothing for both men and women. Another pioneering example is outdoor clothing specialist Patagonia, which runs a roaming pop-up truck across the United States, offering free repairs on any of its products. Patagonia – which took out an ad in the New York Times during Black Friday with the headline “Don’t Buy This Jacket” – asks that customers return their products once they are truly worn out, so they can recycle the fibers and materials as they see best.

Meanwhile, Sweden-based Filippa K is one of the first fashion labels to open its own second-hand store. The boutique in Stockholm retails pre-owned and vintage Filippa K clothing for both men and women. Another pioneering example is outdoor clothing specialist Patagonia, which runs a roaming pop-up truck across the United States, offering free repairs on any of its products. Patagonia – which took out an ad in the New York Times during Black Friday with the headline “Don’t Buy This Jacket” – asks that customers return their products once they are truly worn out, so they can recycle the fibers and materials as they see best.

As “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” looks set to become the mantra for even the wealthiest consumers in future, the pressure is on brands to help us preserve our luxury purchases.